Malnourished Dolphins in Florida Linked to Algae Outbreak Spurred by Human Effluent

In 2013, the Indian River Lagoon in Florida witnessed a disturbing scene as dozens of dolphins mysteriously began to die. Their lifeless bodies washed ashore, revealing the beasts had been emaciated. Fast-forward a decade, and researchers believe they've cracked the case of this bizarre die-off.

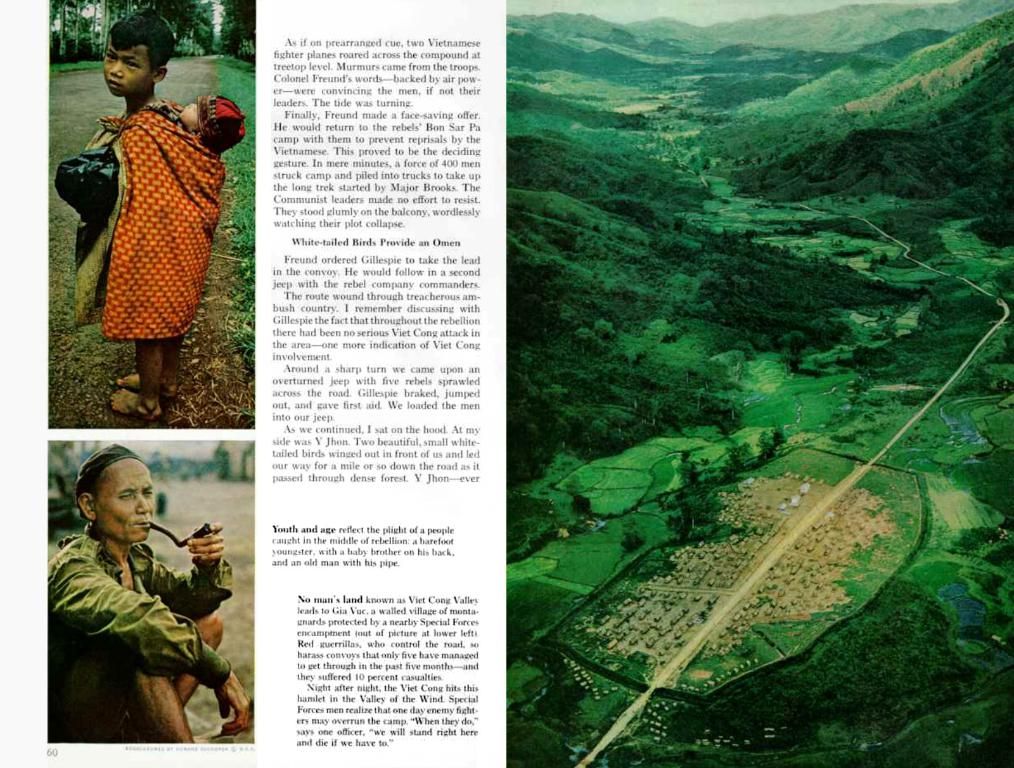

While it's long been associated with gigantic algae blooms, the connection wasn't clear until now. The culprit? You guessed it, humans. Who'd have thought dumping万沽廉necessary garbage and fertilizer into our waterways could wreak such havoc?

Back in 2011, phytoplankton blooms took over the lagoon, causing a radical shift in the area's ecology. The proliferation of mini plant-like organisms slashed the amount of seagrass by over half and hammered the macroalgae (seaweed) population by 75%.

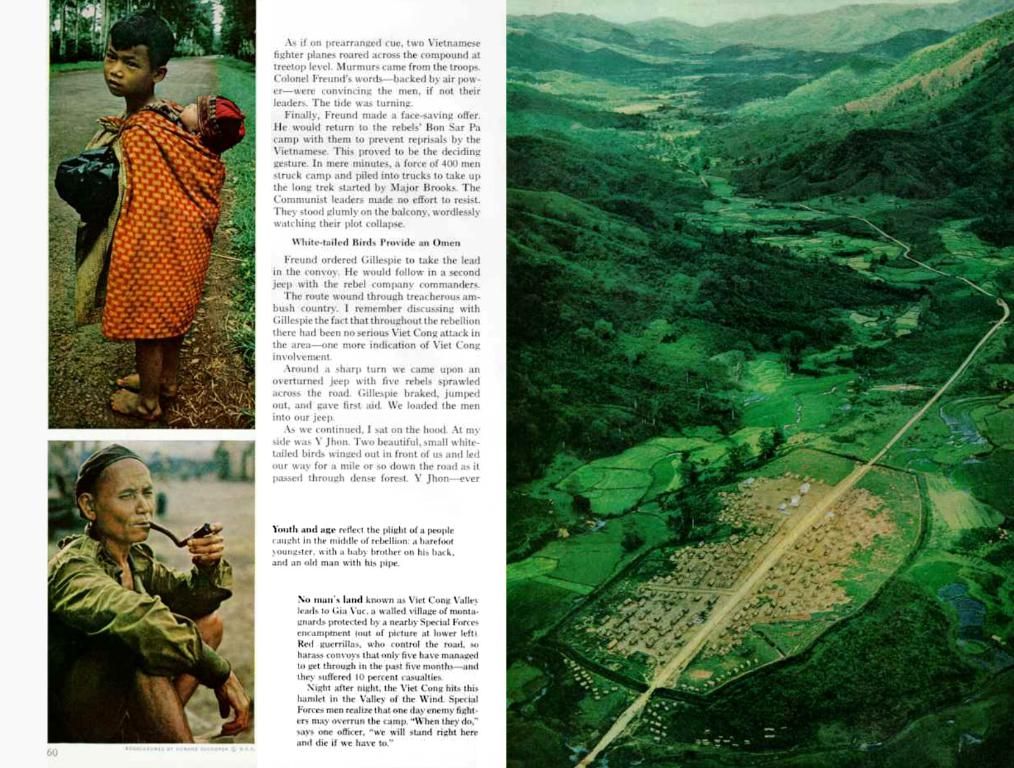

This alone wouldn't have done the dolphins in, but researchers noticed something peculiar when they looked at isotopic ratios in teeth samples taken from deceased dolphins and compared them to teeth from 44 healthy ones. They discovered these poor creatures had drastically altered their diets. The dolphins consumed 14% to 20% fewer ladyfish (their usual diet) but gorged on up to 25% more sea bream (a less nutritious fish).

In essence, the explosion of phytoplankton had scorched the Earth, leaving less food for the dolphins' beloved prey. As their preferred meals vanished, the dolphins were forced to catch more prey to satiate their energy requirements. The consequences of this weren't isolated to the deceased dolphins; they echoed throughout the local dolphin community. At the time, 64% of observed dolphins were underweight, while a staggering 5% were classified as emaciated.

"The shift in diets and the widespread malnourishment suggest the dolphins were struggling to catch enough prey of any kind," explained Wendy Noke Durden, a researcher from the Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute. "The loss of essential habitats may have reduced overall foraging success by altering the abundance and distribution of prey."

According to records, starvation accounted for 17% of recorded dolphin deaths in the region between 2000 and 2020, but that number skyrocketed to 61% in 2013.

"Algal blooms are an integral part of prosperous ecological systems," said Charles Jacoby, a researcher from the University of South Florida. "However, destructive effects arise when the quantities of nutrients entering a system fuel unusually intense, widespread, or prolonged blooms. In most cases, human activities drive these excessive loads. Managing our activities to maintain nutrient levels within safe limits is vital to preventing blooms that disrupt ecosystems."

There is a sliver of good news. The Indian River Lagoon is gradually weaning itself off the toxic waste, and researchers expect safe levels to be reached by 2035. But it's no shocker that our careless treatment of natural habitats can sizzle life out of them-from torching rainforests to chipping away at polar ice to inadvertently importing invasive species to new territories. This is just another sad reminder of the havoc we wreak when we don't pick up our trash.

- The drastic rise in technology-driven algae blooms, such as phytoplankton, in the Indian River Lagoon has been detrimental to the future of its ecosystem.

- The alteration in the food chains due to these blooms, which led to a shift in the diets of dolphins and the depletion of their preferred prey, has been a significant factor in the malnourishment observed among the dolphin community.

- With humans being the primary cause of the nutrient overloads responsible for the intense algae blooms, it's crucial for technology to be used responsibly in conservation efforts to prevent such disruptions in ecosystems.

- As we move forward, the conservation of our Earth's natural habitats, like the Indian River Lagoon, requires a focused approach on managing technology and human activities in a way that maintains nutrient levels within safe limits, ensuring the survival of species like phytoplankton, and the dolphins that depend on them.